Et tu, Panera?

Nandor: Listen to me, little man. From Panera Bread you came, and to Panera Bread you shall return.

I am writing this from a booth near the front corner of Panera Bread café #601651. If you come here at the right time on the right day, you might catch a glimpse of me sitting right here in the same place eating some variant of my go-to meal—today it’s a You Pick Two combination of a Toasted Frontega As best I can tell, this is a made-up word that conveys no meaning beyond the trademark symbol they can slap on it. Chicken sandwich paired with a cup of Mac & Cheese. I visit this place frequently enough that I actually began to earn small discounts and free desserts by signing up for the MyPanera loyalty program. I am neither proud nor ashamed of anything in this paragraph; this is simply a thing that I choose to do.

After following this routine for some time, certain patterns begin to emerge. The same employees preparing orders. The same songs from the overhead speakers. The same ingredients out of stock. The same pair of college students conducting their weekly calculus tutoring session. Even the self-serve ordering kiosk is predictable to the point where I could probably operate it blindfolded if needed.

On kiosks

If you squint, you might assume the kiosk is an iPad due to its familiar size and shape. It is not, and the 4:3 screen’s chunky pixels definitely dispel any notion of that idea. I can’t tell from casual observation who made the tablet hardware, but there is a Verifone card reader/PIN pad combination built into the overall product. Next to this, nominally, a stack of LRS guest pagers on their charging base. In practice, there are frequently no pagers to be had. The idea is perfectly simple: Guests arrive, operate the touch screen to make their selections, pay with a card, then carry a pager to their table to wait for the food to become ready. This self-serve arrangement frees the human cashiers up so they can… not be cashiers, I suppose.

The tablets hold up fairly well considering the amount of customer abuse they’re subjected to. The screens have a protective film of some sort that is only slightly greasy. The tablet is anchored to the countertop by a metal arm that is only a little floppy. And the software, well… Let’s take a brief trip through the ordering flow:

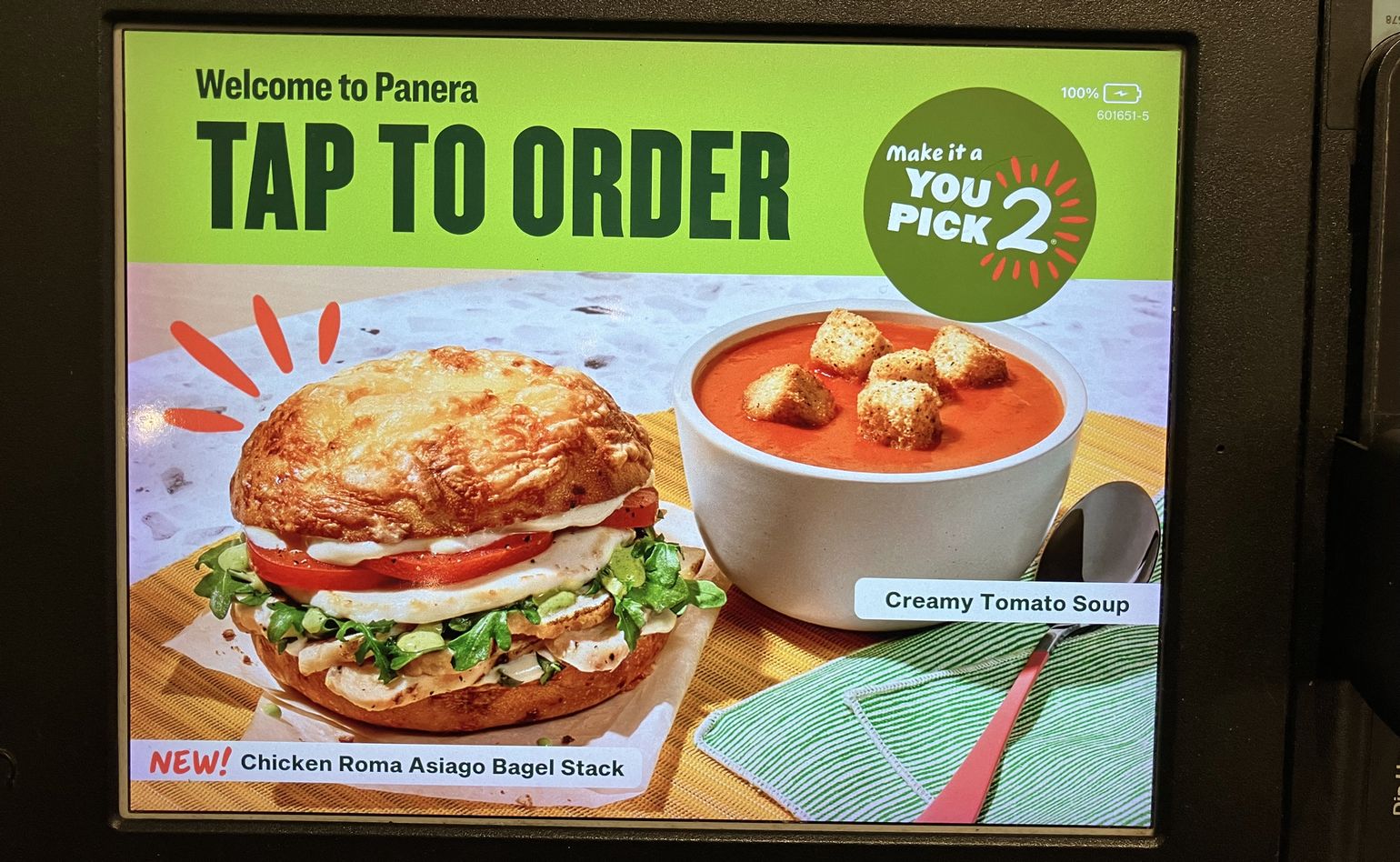

Welcome to Panera; tap to order.

The idle state of the kiosk shows an advertisement for one of the menu options, in this case a pairing of a Chicken Roma Asiago Bagel Stack and a Creamy Tomato Soup. That would be a lot of words to have to say to a cashier. It’s a good thing that the kiosk just lets the user tap on things! Right off the bat, there is a missed opportunity here: There is no place on the screen where a customer can tap to signal their desire to order the thing being advertised. No matter where or how the screen is tapped, there is only one place to go from here:

Sign In to MyPanera, or Continue as Guest. Aside from some other seldom-taken paths at the top and bottom of the screen, these are the choices.

As I am a MyPanera member and wish to avail myself of their loyalty program, I choose Sign In to MyPanera:

Sign in with your phone number. I could also select Email if I was so inclined.

They allow my account to be located by either phone number or email address. The phone number is certainly easier to enter, so that is the option I go with. I key in my ten-digit mobile phone number and tap Next:

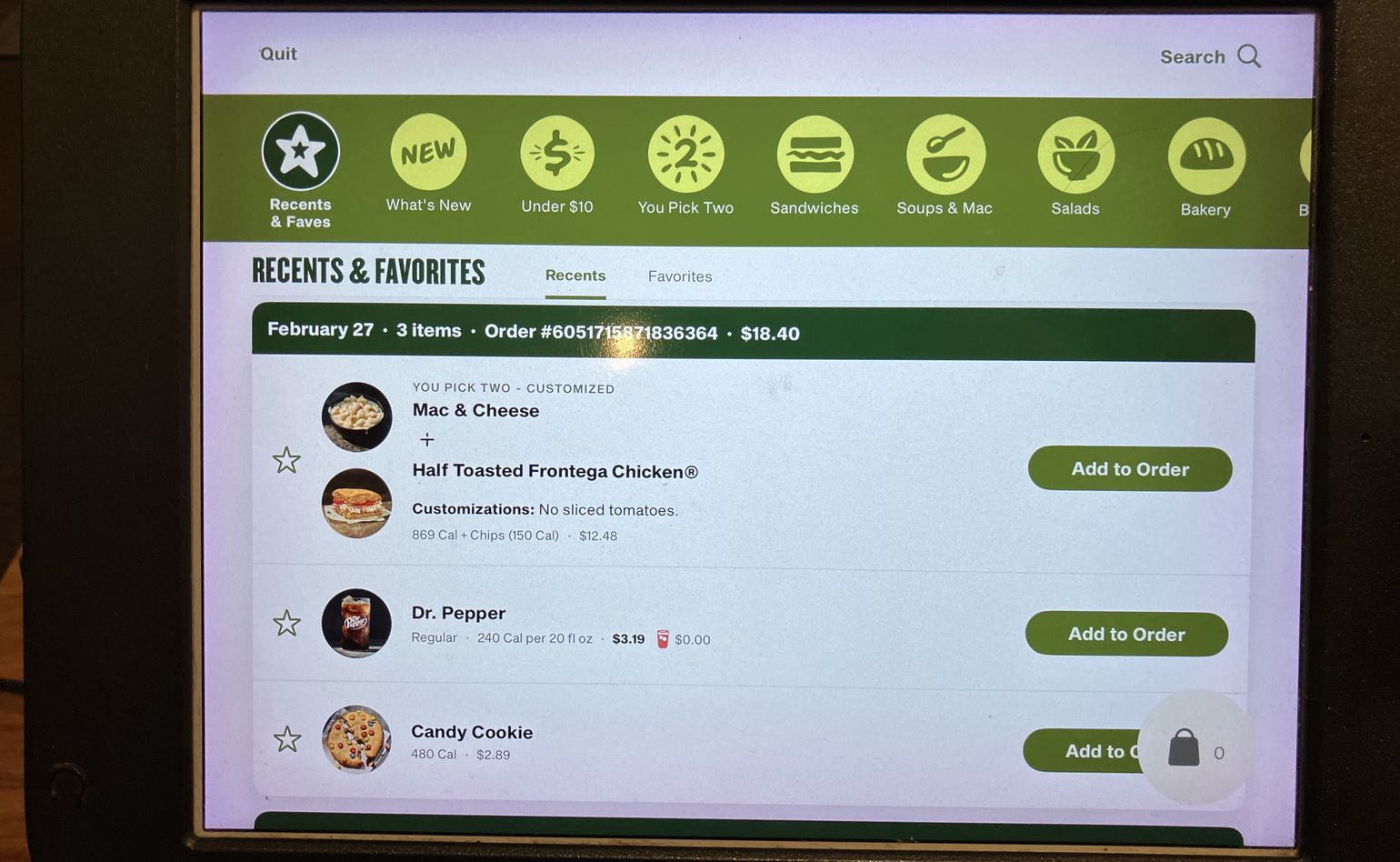

The main ordering interface. The default category displayed is Recents & Favorites and the Recents tab is preselected.

Here is where things get exciting, assuming menu options are the kind of thing that brings excitement into your life. The toolbar near the top of the screen provides quick access to each section of the menu. It defaults to Recents & Faves (short for Favorites) which in my case shows the most recent order I placed on February 27:

- You Pick Two

- Mac & Cheese

- Half Toasted Frontega Chicken, no sliced tomatoes

- Dr Pepper, Technically, the “Dr Pepper” trademark should not have a period. Look it up; I’ll wait. regular

- Candy Cookie

If I scroll down, it remembers even older orders that I had placed while signed in with this phone number. Most of these are substantially the same—in the summer I’ll often get a salad instead, and sometimes I skip the cookie. Similar to the missed opportunity on the initial page, there is no single-tap way to repeat this entire order all at once. The best I can do is tap the three separate Add to Order buttons to resubmit the order piecewise.

Tapping Add to Order on the first item, the You Pick Two, indeed adds it to my running order. It also produces this unwelcome interruption:

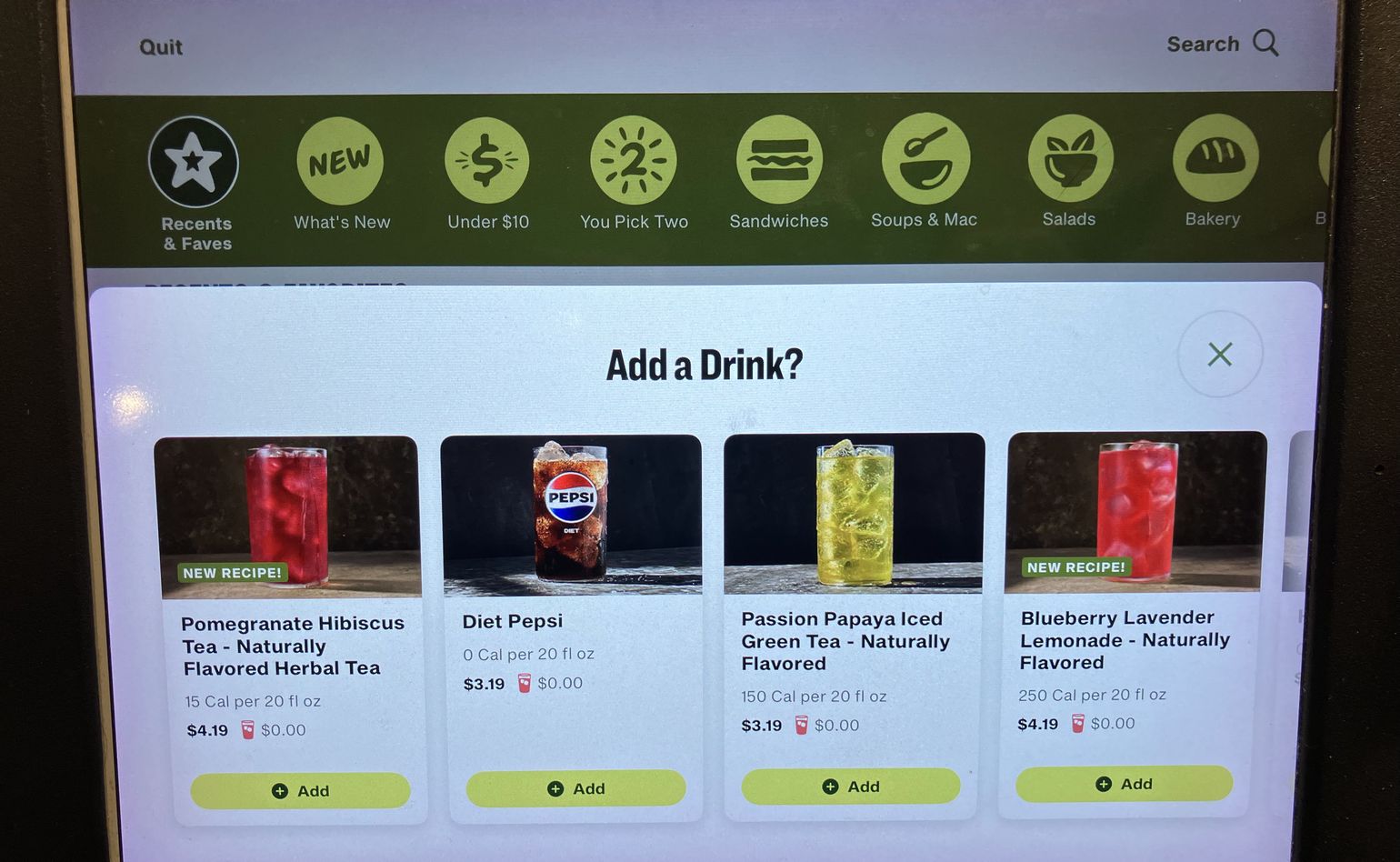

The Add a Drink? bottom sheet.

From the bottom edge, a sheet I briefly considered using the inapplicable term toast to refer to this overlay, making a joke about how the name was apt considering this café smells faintly like burnt bread. But my penchant for pedantry would not permit this. slides in to obscure almost all of the important content on the screen. The ordering flow helpfully assumes I want to add a drink to my order, while unhelpfully suggesting four things I have no intention of ever drinking: Pomegranate Hibiscus Tea, Diet Pepsi, Passion Papaya Iced Green Tea, and Blueberry Lavender Lemonade. Nice work with the superfluous “Naturally Flavored” verbiage on the teas and lemonade. It’s like reading the keyword spam on the end of every Amazon product name. The thing that makes this particularly absurd is that they already know what I probably wanted to pick. The Dr Pepper—the button I would’ve been pressing right now if they hadn’t covered it up with this irrelevant and thoughtless distraction—would’ve been a perfect option to slide into one of these spots. But it wasn’t done.

The right edge dimly suggests Perhaps too dimly. It is pretty easy to miss the fact that this content can be scrolled when you’re in a rush. If you do bother to scroll, there is exactly one additional item to see, along with a “show everything” button that takes you away from the recent orders screen. that there is more content to be discovered in this list if I scrolled it in that direction. But by this point I’m not in a discovery kind of mood. I dismiss this useless obstruction and return back to the ordering interface which has remained essentially unchanged. I tap the next Add to Order button to add the Dr Pepper to my order. Predictably, another bottom sheet covers the screen:

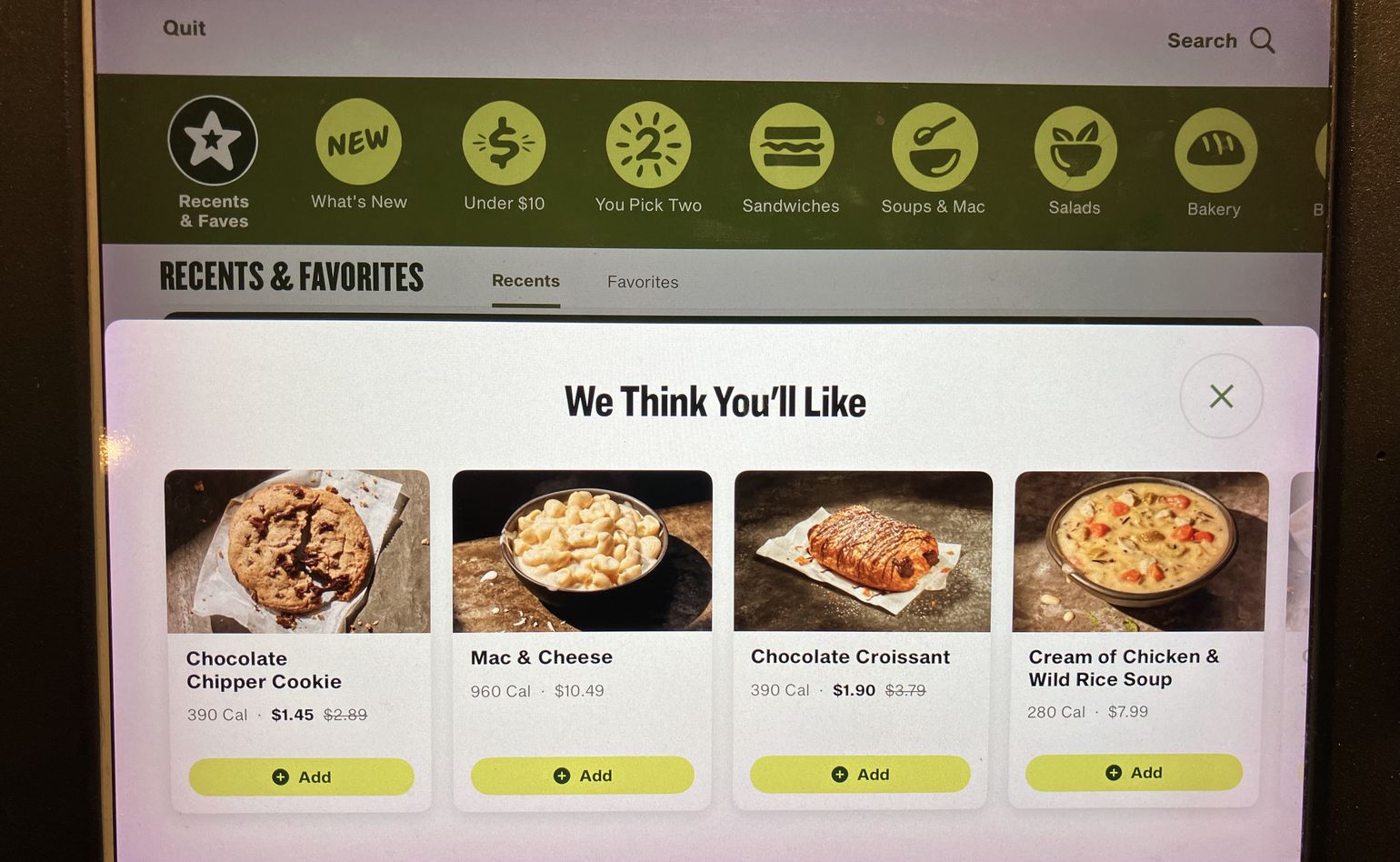

The We Think You’ll Like bottom sheet.

I could make a similar observation here about how none of the options presented are the Candy Cookie that I am likely to want to add based on its presence on the order screen. Instead, I’ll point out that this list is recommending adding the Mac & Cheese that is already in my accursed order. Do they really think I will “like” the Chocolate Chipper Cookie, the Chocolate Croissant, or the Cream of Chicken & Wild Rice Soup given any of my interactions up to this point? Have they even thought at all?

Similar to the previous sheet, this one is summarily dismissed so the Candy Cookie I actually wanted can be selected from the same main ordering interface that the rest of the order was assembled from. Oddly enough, this third addition does not produce a new set of interrupting suggestions.

From this point, the ordering process is fairly uneventful. It shows a summary of the order, prompts for dine-in or take-out, asks me to pick up a pager If I can find one. and enter its number, and it provides me the option of using my phone number for text updates about the status of the food’s preparation. Even though it was generous enough to auto-fill this box with the phone number I used to sign into MyPanera, I decline to use this particular feature.

On micro-indignities

Without knowing anything about the team structure or engineering culture that produced this software, I have a hunch that a Gerald Weinberg quote would describe the circumstances that led to this product’s behavior fairly well:

“Things are the way they are because they got that way.”

It doesn’t seem like there was a deliberate choice made to have the software work this way. It is more likely that an absence of choices led to this.

By examining other paths through the kiosk software flow, it becomes apparent that the suggested options are always basically the same, and their sheets are always raised at the same points in the order flow. And critically, the suggestions behave the same whether the user has signed into MyPanera or if they are ordering as a guest. In the specific context of an interaction with an anonymous guest, the suggestions almost make sense: These are likely some of the most popular or must lucrative items on the menu, so it stands to reason that showing them to a random stranger might help them make a decision that all parties can be satisfied with.

The problem is the blind, unilateral application of that same shot-in-the-dark logic to loyal customers who already know the menu and whose entire order history can be retrieved and analyzed. It would not be terribly difficult, from a software complexity standpoint, to add a conditional check that says “hey this person has ordered from us before, let’s skip showing them this junk.” And it would not be an insurmountable feat of engineering to go above and beyond to “hey this person orders something with chicken every time, let’s show them all the chicken dishes we have.” With all the machine learning and LLM noise currently being crammed into every facet of daily life, it’s frankly incredible how offensively dumb this interaction really is.

And it is not simply that they are dumb. They are also unavoidable—inevitable. Sure as the sun rises in the east, the kiosk at Panera is going to propose the same irrelevant “helpful” suggestions that it should already know I don’t want and it is going to waste a tiny sliver of my time by doing it. Over and over. At least until the software is rewritten to make it equally awful in some new way. Or until Panera goes bankrupt and gets hollowed out by some private equity firm. Or until my arteries, clogged up from all that mac and cheese, get hollowed out by some cardiologist.

This happens all the time. Websites cover important content with pointless auto-playing videos and desperate pleas to sign up for mailing lists. Miscalibrated supermarket self-checkout machines constantly admonish “place your item in the bagging area” after every item is scanned, as if the customer forgot how to do that in the ten seconds since the last time those words were repeated. The self-service gas pumps at the convenience store run at a glacial pace when handling the transactional aspects of purchasing gasoline, then play perfectly fluid HD-quality advertisements with crystal clear (and unjustifiably loud) audio the rest of the time. Here’s a little life hack: Frequently these will be a particular Gilbarco Veeder-Root model, identifiable by a strip of four buttons on each side of the screen. The second button down on the right strip mutes the audio. There is, of course, absolutely no on-device indication that this option is available.

It’s fairly straightforward to look at software in terms of what it does. There are clear ways to measure whether a software product works or not, and if it is succeeding at achieving some stated business goal. It’s much harder to measure how software makes people feel, especially when any given interaction with a single piece of software, measured in a vacuum, is but a single paper cut in the daily barrage of thousands of subtly awful human-computer interactions that conspire to slice us all to death.

On souls

Believe it or not, I was educated in a staunchly Christian school environment from the ages of five to about ten years old. It didn’t take, to say the least. I’ll admit that it’s likely I was a poor student, but I’m also sure the teachers shared some of the blame as well. Long story short, I have a fragmented and distorted understanding of the beliefs, but some of it stuck.

One of the things that they really tried to drill into me was the idea that I had a soul—something that comprised everything that was not part of my physical being. The body would one day grow old and die, but the soul would live forever. If I walked a good and righteous path, that soul would be rewarded with eternal life in a heaven that kinda looked like a cloudy plane ride over Nebraska. This led to questions like, how does eternal life feel if there is no body to experience it in? Are there mirrors or reflective surfaces, and what might I see if I looked at myself in them? Would I be a young person or an old geezer like how I was when I died? Will I have hands and feet?

This environment was also very adamant that I, and I use their exact phrasing, “ask Jesus into my heart.” This was apparently a prerequisite to earning the whole heaven thing, despite the fact that, as I understood it, the heart was part of the physical body that would eventually end up in the garbage heap with the rest of my cold meat parts. Looking back, they probably meant it in a metaphorical sense, although they did frame the act with such immense and profound solemnity that it really felt like accepting Jesus was akin to losing one’s virginity. Can’t go back once that trigger has been pulled, so you’d better really mean it. I had always understood the heart and the soul to be two different things—otherwise why would both Huey Lewis and T’Pau have recorded songs about them being separate from each other?

Technically, I think I got thrown out of that school for that kind of thinking (among other things). Some of the lessons stuck, but overall they failed to mold me into a gospel-spreading missionary with twelve children. They did manage to instill a moral compass and they did successfully teach me phonics. So I guess it all worked out.

For all the time spent thinking about it, I still don’t know in an absolute sense what a soul is. I probably have one, lots of people would say a ficus tree probably does not, and maybe it’s a coin flip as to which way it goes for dogs and cats. So ensoulment is somewhat proportional to sapience, maybe. Who the hell knows.

One thing is clear, though: Human-made objects have no souls. Right? The brutalist architecture, soulless. Modern music, missing its soul. The movie Tenet, utterly lacking in soul. But not every building, song, or movie earns such criticism, so there must really be some genuine quality of “soul” that inanimate things can effuse. It couldn’t be a consciousness thing and it’s not religious either. It’s evidently something these items have that is separate from the tangible matter they’re made from. The colloquial soul.

So, let’s play with this idea a little. If my human soul is everything that is not my physical body, that just leaves my consciousness, perceptions, values, morals, those types of things. But to the outside world, most of that stuff doesn’t actually matter all that much. Nobody else gets to see or know or feel anything I carry inside myself. The only way to make any of that mean anything is to perform some kind of action in the world. Toss a pine cone, tell a story, make somebody else feel something. Exercise my agency. If I don’t make a mark on the outside world, everything soulish inside of me is basically irrelevant to the rest of the universe. This is broadly compatible with the idea that the person who devotes their time to rehabilitating injured birds gets to go to heaven, while the dirtbag who steals donated toys and vandalizes public libraries is likely more hellbound.

This, then, pulls in a bunch of questions about morality and exactly why the bird thing is good while the theft/vandalism thing is bad. But maybe we can hand-wave that away by saying that things are good if they affect other people in ways that make them feel good, and things are bad if they make people feel shitty.

By completely misapplying this model to the Panera kiosk software, I could work backwards and propose that it does have a form of soul, and its soul is ever-so-slightly malignant because it annoys me and cultivates small embers of negative emotions. If I were to suggest banishing it to the deepest pits of hell, perhaps that would be seen as a bit harsh. But I’d be really surprised if anybody proposed sending it to heaven instead.

On influence

I’m going to make a wild assumption and proclaim that every single person who designed and built the Ford Model T (1908–1927) is now dead. Yet you can go out into the world today and, with a bit of effort, find one of these vehicles in perfect operating condition. If you play your cards exceptionally well, perhaps you could even drive one yourself. This car has a joyful soul. It’s impressive to see, a bit goofy looking, certainly worthy of being photographed and shared with friends to brighten somebody else’s day.

The soul of an object, and that of a person when you get right down to it, is shaped by the sum of the things that were put into it. Lived experience for people, design and manufacturing choices for objects, and the long slow march of time for both. These inputs are then reflected back on the world where they eventually influence the souls of other people and things. Everybody and everything we encounter in life was shaped in uncountably many tiny ways by the souls of the people and objects experienced along the way.

A thousand miles away, in the wooded corner of an overgrown field, another Model T lies buried under layers upon layers of thick kudzu vines. It has been abandoned, forgotten, completely released from its former useful purpose. The soul of this one is mournful. It’s a reminder that, whether to dust or rust, everything decays. Or that’s what its soul would be like if any attention were being paid to it.

A soul can slowly lose its influence over its environment. The kudzu doesn’t really care about the car beyond the physical structure it provides. The previous owners of the land have packed up and moved away, forgetting all about what they left behind. It would require some sort of absurd metaphysical position to try to argue that the car no longer existed at all, but its soul is languishing under there. If it were capable of feeling, perhaps frustration and despair about the relative pointlessness of its existence. Still, perhaps it is providing a home to some insects. Maybe the flakes of iron that fall to the earth are providing micronutrients to future crops. Whatever lives here in the future, it will have been sheltered and nourished by a once-proud road-faring machine. In time, this soul will return in some other form.

Perhaps a cleaner example would be a story, handwritten on a sheet of loose paper. Folded in half, tucked into a hardcover book, and placed on a shelf. The paper unambiguously exists, as do the bits of ink that have been absorbed into the page. The information represented by that writing—the world and characters of the story—all these things exist. But until the story is actually read by somebody, it is unable to have any real effect on anybody. Right now nobody is thinking about that setting, nobody feels anger toward the antagonist, nobody experiences the rush of anticipation for what happens next. Without a reader, the soul of this story is stymied.

Even a computer program can be viewed as an expression of the programmer’s own ambition. Programming is essentially the act of instructing a machine to do something that the programmer could do themselves. Given enough time and scratch paper, that is. In expressing this ambition, the programmer leaves an imprint of their soul in every line of program code they write. Different people, and their different souls, would write the same code in subtly different ways. Neither way is the “best” way; each is simply the most fitting home for the piece of soul it now carries. Such code is ultimately spread out into hundreds of thousands of tiny regions of electrical charge trapped on nanoscopic islands of metal inside a flash memory cell. When the computer is powered down at the end of the day, these pockets of electrons still exist. But what effect can the code’s soul have on the outside world while it’s stuck in there?

Incidentally, this may be why it’s common to hear people in software engineering and adjacent professions talk about feeling somewhat unfulfilled in their work. It is painful to put a piece of your soul into an electronic form only for it to become trapped in there long term. It is soul-crushing to spend time creating Power BI dashboards that nobody opens. Developmental psychologists generally agree that humans form a sense of object permanence by the time we’re a few months old, but I don’t believe anyone truly develops to the point where they ever become completely okay with the idea of grating little pieces of their soul into acts that don’t mean a damn thing at the end of the day.

On responsibility

There is a flip side to this coin. Sometimes you find yourself in a position of enormous influence. Perhaps you get to draft a consequential piece of government policy. Maybe you are tasked with recording the next 1-877-KARS-4-KIDS radio jingle. Also… Isn’t that way too many digits for a phone number? Other times you’re just working on the kiosk software for a multinational fast-casual restaurant chain. You have a certain ethical responsibility to make sure you’re not accidentally (or intentionally!) creating something with a wicked soul.

Overreactive? Nah.

Imagine you had an acquaintance who acted the way that so many pieces of technology behave. A person who constantly interrupts conversations with their irrelevant and conceited self-promotion. Somebody who refuses to learn your tastes and preferences and repeatedly goes out of their way to present options that run contrary to them. The sort of conversationalist who takes too long to respond to anything you say but always manages to produce a perfectly useless and frustrating answer. A real piece of shit who vacillates wildly between calculated gaslighting and incompetent lumbering, slowly chipping away at your sense of agency either way. If this person were real, you’d probably want to push them in front of a train. This hypothetical acquaintance—this malevolent soul—is a source of negative emotions. This is not somebody you want influencing your own soul.

Technology ain’t much different. Countless keys have been struck about the myriad ways everything sucks, and I feel it would not be a good use of anybody’s time to beat that particular horse corpse here. But I feel that we all really should spend more time thinking about the way this stuff makes us feel as we navigate each day, and how it continues to affect us long after we have moved onto the next task. Spend some time people-watching and observe how the average user engages with these interfaces. Watch them get stuck going in circles due to non-obvious loops in the menu architecture. See how the touch screen misreads slow or timid taps as drag interactions instead. Witness the type-ahead dropdown list rearrange itself unexpectedly, burying the desired choice in an ocean of disordered nothings. But even more importantly, focus on the people. Really take in the body language, the sighing, the progressively aggravated screen taps. Watch as they turn and leave; do they seem angrier than they were before they got there? Even Panera leaked everybody’s data. What reasonable person doesn’t get a little ticked off that this keeps happening?

Much like our asshole human acquaintance, these products have malevolent souls and they are eminently capable of causing real and lasting negative emotions in people. Perhaps no single piece of software has the same outsize impact that one obnoxious person might have, but the cumulative effect of all these product interactions gradually becomes something directly comparable. It’s more insidious, because we don’t really notice it happening moment to moment. But try to think back… When was the last time you had to change your address or phone number across all your online banking and shopping accounts? Which sites required you to update your password for no reason? Which ones sent a security code via email or SMS that didn’t arrive in a timely manner? Which of the sites had an impossible-to-navigate menu structure with a nagging chatbot that was worse than useless? Which sites pressured you to take a tour of new features, tried to get you to commit to changing a setting, or goaded you into doing something you didn’t really want to do? How did you feel after enduring these experiences? How do you feel right now, imagining the hypothetical world in which you have to do all that over again?

This article is being written on an Intel MacBook Pro that I refuse to upgrade to macOS Sequoia simply due to my own intransigence. At the time of this writing, macOS Sonoma is still supported and still receiving security fixes. It will continue to be supported until probably Fall 2026. I am committing no crimes here. At least twice a week, I am prompted to upgrade my operating system. The options available to me are “Yes” and (tacitly) “Bother Me Again In Three Days.” There is no other choice. There is apparently no workaround to silence this recurring notification. Until the non-replaceable battery finally ages to the point where I can’t make it through a complete Panera trip without needing to charge, those are my options. “Yes” or “You Have No Choice.” “Yes” or “We Know Better Than You.” “Yes” or “Get Bent, Idiot.” This interaction has the soul of an asshole who doesn’t take no for an answer. Somebody or some group of somebodies imbued it with that.

Now, I could take myself down to the local grocery store and pile a couple of shopping carts up in the middle of one of the aisles. I reckon I’d be able to annoy a couple dozen people before the store manager comes by and forcibly removes me. I would like to believe that whatever virtue I carry in my soul would not allow me to actually do that. I could then, with a bit more effort, get myself hired to work on an operating system or user-facing app or website where I implement something equally useless, counterproductive, annoying, or rage-inducing. By virtue of my position working on such a popular or important product, I could broadcast that obnoxious mood to potentially millions of people all at once. And nobody in any position of authority would stop me. As long as the revenue graph pointed the right way, they would praise me for it. What would my soul have to say about that?

Is it any solace to know that the people who design and build these products might not even use them in their daily lives? There have been accusations—apocryphal for all I know—that even Microsoft designers use Mac computers instead of Windows PCs. I’m sure everybody reading this can recall a time when they have endured some kind of technical training where it was clear the presenter didn’t really know how to use the software either. Speaking only from personal experience, I don’t believe I have ever worked on any product of any appreciable size where any single person in a position of leadership had a holistic understanding of the entire thing. And it basically didn’t matter; the shambling mess still worked in the end, for some definition of “worked.” Is that really the bar we all aspire to? To use awful tools and processes to poop out something that “works” so we can make some money then wander off to be too spiritually drained to do anything else?

Things are the way they are because they got that way. There’s an underlying reason for the shared sentiment of “I’d rather be unemployed than create another Workday account.” Nobody out there can precisely quantify how many of these tiny indignities equate to a punch in the stomach, or exactly how many of those punches it takes to reach a state of complete emotional breakdown. But we all seem to be inching closer to figuring this out empirically every time we have to face one of these defiled, grotesque souls.

God save them all.

« Back to Articles